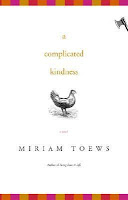

I have to say that when books have been foisted on me they make much less of an impression on me than when I choose to pick them up. This is unfortunately the case with the much-acclaimed Catcher in the Rye, reputed to be the epitome of the coming-of-age novel, which I read in high school and no longer remember anything about, other than it leaving me with a vague sense of distaste. But others - like Ian McEwan's Atonement and Miriam Toews' A Complicated Kindness - have that depth-of-knowledge-but-lack-of-emotional-maturity balance happening in them that just floor me.

Crimes horticoles is sort of the same way: Emile, the protagonist, is home-schooled by a well-travelled adventurer Frenchman and is obviously highly knowledgeable in some domains. The novel is in the first person, and Emile's voice is screaming "listen to me, I know big fancy words!" to such an extent that I'm sometimes tempted to explain the references to quattro-cento painters and the Chiaroscuro technique in parentheses, and sometimes I just want to go and give her a good shake for using "Gastropod" over the more accessible "snail."

|

| Gastropod |

No comments:

Post a Comment